An End to Humbugism

03.12.16

Mark Perryman provides a seasonal round-up of the best books to cheer up the radical spirit

From #chaoticbrexit to the triumph of Trump via the summertime Labour coup. 2016 will be a year to forget for many who cling on to an optimism that a better tomorrow remains not only necessary but possible too. The toxicity of racism , the brutal closure of the Calais refugee camp, the political murder of Jo Cox, the human disaster unfolding in Syria and ever-increasing landmass temperatures signalling the onward march of Climate Change. More than enough to have us all digging into our pockets for the humbugs while giving the holly and the ivy this year a miss. But there’s another side to all of that, for every setback there’s a fightback and in and amongst the mix more than enough to keep at least a semblance of belief in a radically different future. There’s always next year after all.

Britain, across Europe, the USA progressives are now up against a Populist Right, which requires a Populist Left in response. The Populist Explosion by John B. Judis is a richly analytical account of the similarities and differences of what this year emerged as a global phenomenon of racist reaction while Europe in Revolt edited by Catarina Príncipe and Bhaskar Sunkara reveal the resources of hope an insurgent European left provides. For the prospects of ‘what might have been’ read Our Revolution by Bernie Sanders and imagine what a President Trump-free 2017 might have looked like.

Such an alternative right now however remains at a very low ebb. Books that begin to map out the beginnings of a journey back are needed more than ever. Fortunately 2016 began to provide a good variety of such handy volumes. Now out in paperback Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism remains for many the best of the bunch and for those who don’t have it already a must-have for any Christmas radical reads shopping list. A personal favourite for the combination of design, format and writing is ABCs of Socialism edited by Bhaskar Sunkara. A book to bring the optimist back to earth is The Corruption of Capitalism by Guy Standing, pioneer of the ‘precariat’ analysis, who continues his well-studied research to reveal the transformation of work being effected via the rentier economy. An updated edition of the trailblazing Inventing the Future from Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams provides a manifesto of change to counter the miserable terms and conditions Standing’s ‘precariart’ are forced to endure. But of course these conditions aren’t created simply by the world of work, edited by Jeremy Gilbert Neoliberal Culture provides a much-needed breadth of critique that takes our understanding of the neoliberalism beyond any tendency to cling on to a workerist model of explanation. Taking a similarly broad scope is author Mark Greif, the title of his new book rather gives this away, Against Everything, the perfect seasonal gift for oppositionalists everywhere, not that they will appreciate the gesture, being against such fripperies after all.

Such an alternative right now however remains at a very low ebb. Books that begin to map out the beginnings of a journey back are needed more than ever. Fortunately 2016 began to provide a good variety of such handy volumes. Now out in paperback Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism remains for many the best of the bunch and for those who don’t have it already a must-have for any Christmas radical reads shopping list. A personal favourite for the combination of design, format and writing is ABCs of Socialism edited by Bhaskar Sunkara. A book to bring the optimist back to earth is The Corruption of Capitalism by Guy Standing, pioneer of the ‘precariat’ analysis, who continues his well-studied research to reveal the transformation of work being effected via the rentier economy. An updated edition of the trailblazing Inventing the Future from Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams provides a manifesto of change to counter the miserable terms and conditions Standing’s ‘precariart’ are forced to endure. But of course these conditions aren’t created simply by the world of work, edited by Jeremy Gilbert Neoliberal Culture provides a much-needed breadth of critique that takes our understanding of the neoliberalism beyond any tendency to cling on to a workerist model of explanation. Taking a similarly broad scope is author Mark Greif, the title of his new book rather gives this away, Against Everything, the perfect seasonal gift for oppositionalists everywhere, not that they will appreciate the gesture, being against such fripperies after all.

After that little lot the season of not enough goodwill and too little peace may require a bit of cheer-me-up. The Candidate by Alex Nunns should do precisely that for the convinced Corbynite with an account in riveting detail of Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to power which reads more like a thriller than a chronicle, and that’s a compliment by the way! And for the year ahead those plotting the downfall of Corbyn’s opposition from the Labour Right have the perfect Christmas present in the way of David Osland’s rewrite of the activist classic How to Select or Reselect Your MP. The annual Socialist Register 2017 edition is entitled Rethinking Revolution with a range of fresh thinking on a great theme ranging from Corbynism , the European Left and South Africa’s ANC to radical change in Bolivia plus a range of essays questioning the legacy of 1917’s revolutionary model.

Of course in 2017 there’ll be no escaping the centenary of the Russian Revolution. Get ready to make it a revolutionary New Year with the classic dissident account, Victor Serge’s Year One of the Russian Revolution or for a wholly original approach treat yourself to the brilliant comic-strip style approach of 1917: Russia’s Red Year by Tim Sanders and John Newsinger. Quite the quirkiest account of 1917 I’ve read though, and all the better for it is Catherine Merridale’s incredibly original Lenin on the Train which describes Lenin’s journey to the revolution as a kind of communist version of great rail journeys, superb. The latest edition of my favourite journal Twentieth Century Communismhas a particular interest in communist nostalgia ranging over instances of this perhaps not very quaint phenomenon in Romania, Italy Greece and elsewhere. Without decrying the historical significance of the Russian Revolution there are plenty of other starting points for the revolutionary impulse. The Leveller Revolution from John Rees expertly and passionately describes the tumultuous times of the 1640s English Civil War as one such starting point. Not exactly a year of revolution but one of change nevertheless David Stubbs in 1996 & The End Of History chooses the year of Blur, Oasis, Three Lions and the eve of Blair as PM to entertainingly conclude that those particular twelve months were a kind of start for what became postmodern Britain.

Of course in 2017 there’ll be no escaping the centenary of the Russian Revolution. Get ready to make it a revolutionary New Year with the classic dissident account, Victor Serge’s Year One of the Russian Revolution or for a wholly original approach treat yourself to the brilliant comic-strip style approach of 1917: Russia’s Red Year by Tim Sanders and John Newsinger. Quite the quirkiest account of 1917 I’ve read though, and all the better for it is Catherine Merridale’s incredibly original Lenin on the Train which describes Lenin’s journey to the revolution as a kind of communist version of great rail journeys, superb. The latest edition of my favourite journal Twentieth Century Communismhas a particular interest in communist nostalgia ranging over instances of this perhaps not very quaint phenomenon in Romania, Italy Greece and elsewhere. Without decrying the historical significance of the Russian Revolution there are plenty of other starting points for the revolutionary impulse. The Leveller Revolution from John Rees expertly and passionately describes the tumultuous times of the 1640s English Civil War as one such starting point. Not exactly a year of revolution but one of change nevertheless David Stubbs in 1996 & The End Of History chooses the year of Blur, Oasis, Three Lions and the eve of Blair as PM to entertainingly conclude that those particular twelve months were a kind of start for what became postmodern Britain.

To understand the evolution of an historical tradition of thought and action there’s no better collection than the recently re-issued Antonio Gramsci Reader. This peerless thinker and revolutionary ’s writings 1916-1935 remain the single most important application of 1917 to the world after WWI coinciding with the rise of interwar fascism, moreover they have stood the test of time better than most. A new collection of Eric Hobsbawm’s writings on Latin America Viva La Revolucion is a wonderful way to explore how interpreting the world can enable us to change the world, to kind of misquote Marx. Today such a philosophy, what was once called praxis, finds many different expressions in varied locations and situations. One example is activist-photography on the frontline between the state of Israel and Palestinian resistance which is the subject of Activestills edited by Vered Maimon and Shiraz Grinbaum.

In 2016, as in 2015 and 2014 were too the pivot of radical change on this island remains Scotland. Voted against #ToryBrexit , for a social-democratic and green majority in favour of Scottish independence, led by the most impressive by far of all domestic party leaders. It is no surprise then that writing on Scotland and its politics produces some of the most thoughtful insights either north of, or all points south, of the border. Neil Davidson’s latest collection of richly intellectual essays Nation-States reinforces his reputation as the most creative author currently writing out of the Marxist tradition on the theories and intersections of a nationalist politics. Davidson’s writing combines critical analysis with a grand global overview. Scotland the Bold by Gerry Hassan is focussed more specifically on Scotland yet this liberates rather than restricts Gerry’s radical imaginary which he brilliantly applies to the present and future of this most turbulent of nations.

In 2016, as in 2015 and 2014 were too the pivot of radical change on this island remains Scotland. Voted against #ToryBrexit , for a social-democratic and green majority in favour of Scottish independence, led by the most impressive by far of all domestic party leaders. It is no surprise then that writing on Scotland and its politics produces some of the most thoughtful insights either north of, or all points south, of the border. Neil Davidson’s latest collection of richly intellectual essays Nation-States reinforces his reputation as the most creative author currently writing out of the Marxist tradition on the theories and intersections of a nationalist politics. Davidson’s writing combines critical analysis with a grand global overview. Scotland the Bold by Gerry Hassan is focussed more specifically on Scotland yet this liberates rather than restricts Gerry’s radical imaginary which he brilliantly applies to the present and future of this most turbulent of nations.

The dark side of versions of nationalism rooted not in liberation but blood and soil are covered in two powerfulyl critical memoirs. Gaby Weiner’s Tales of Loving and Leavingdeserves to become a modern classic. This is a book that expertly yet effortlessly weaves family and generation into two of the most epic events of the Twentieth Century, the Russian Revolution and Hitler coming to power while linking both to a consequence that we continue to live with in the 21st, mass migration. Fascist in the Familyis the kind of title to get the reader to sit up and take notice before they’ve even started thumbing through the pages. Left-wing writer Francis Beckett retells the story of his father, elected as Labour’s youngest MP at the 1924 General Election he became one of Oswald Mosley’s key allies in the British Union of Fascists until he found even this lot not Nazi enough and helped found the National Socialist League. Told with a brutal honesty, a book of horrific tragedy.

The dark side of versions of nationalism rooted not in liberation but blood and soil are covered in two powerfulyl critical memoirs. Gaby Weiner’s Tales of Loving and Leavingdeserves to become a modern classic. This is a book that expertly yet effortlessly weaves family and generation into two of the most epic events of the Twentieth Century, the Russian Revolution and Hitler coming to power while linking both to a consequence that we continue to live with in the 21st, mass migration. Fascist in the Familyis the kind of title to get the reader to sit up and take notice before they’ve even started thumbing through the pages. Left-wing writer Francis Beckett retells the story of his father, elected as Labour’s youngest MP at the 1924 General Election he became one of Oswald Mosley’s key allies in the British Union of Fascists until he found even this lot not Nazi enough and helped found the National Socialist League. Told with a brutal honesty, a book of horrific tragedy.

To add some fiction over the holiday break Andrew Smith’s The Speech . Taking as its starting point the real-life Enoch Powell ‘Rivers of Blood’ tirade Smith engages with themes of culture and community to reveal a fictional plot rooted in reality and hope. Originally published in the wake of Italy’s ‘Hot Autumn’ of 1969 the novel We Want Everything by Nanni Balestrini is both framed by this period of revolutionary youth culture but not trapped by it. As such, this is a novel of enduring inspiration as well as a riveting portrayal of revolt. Europe today is a very different place to ’69 and for a chunk of the British electorate they can’t leave the continent quick enough. Bruno Vincent’s pastiche Enid Blyton story Five on Brexit Island is the near perfect stocking-filler for politicos, remainers or leavers alike.

But why should the grown-ups have all the best books? A new Michael Rosen is the highlight of almost any Christmas for younger readers and his latest Jelly Boots, Smelly Boots will do anything but disappoint. Newly translated, An Elephantasy by Argentine children’s author María Elena Walsh combines surrealism and humour via an adventure that is every bit as revealing as it is funny.

But why should the grown-ups have all the best books? A new Michael Rosen is the highlight of almost any Christmas for younger readers and his latest Jelly Boots, Smelly Boots will do anything but disappoint. Newly translated, An Elephantasy by Argentine children’s author María Elena Walsh combines surrealism and humour via an adventure that is every bit as revealing as it is funny.

Even post Bake Off sell-off Christmas is arguably more than almost anything else a culinary event. For those looking to go past the Delias and Jamies three cookery books to expand any chef’s horizons. Ideas to make a break with the traditonal yuletide fare, or simply spice up mealtimes the whole year round, are aplenty in Meera Sodha’s new book Fresh India. Looking beyond Christmas the latest Leon book Happy Salads by Jane Baxter and John Vincent will have any wannabe chef eagerly awaiting Spring to try out the vast range of recipes offered for warmer days. Substantially updated and entirely redesigned the second edition of Laila Ed-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt’s The Gaza Kitchen is internationalism as you eat. History, politics and delicious recipes for those who like to cook up some solidarity.

For agifts to put under the tree for the activist who is anti-consumerist until he, or she, realises that means no pressies we recommend the new edition of Verso’s Book Of Dissent will have ‘em whooping with revolutionary delight not just on the 25th but for the next twelve months too. Or if a different kind of inspiration is required one from Michael Rosen for all from young adults to fully fledged grown-ups, What is Poetry? An easy-to-follow guide to both reading and writing poems, perfect for those with the secret ambition of releasing the inner rhyming couplet. Though our favourite gift is another from Verso, their 2017 Radical Diarydestined to resurrect the annual Big Red Diary that some of a certain political age will remember with fondness. Luxurious design, historical dates and details, quotes, illustrated throughout, it has enough to turn the most dogged pessimist into an optimist for the year ahead.

And our book of the seasonal quarter, our number one for Santa’s red list? Well we have two not one because we’ve chosen a theme and there is a pair such outstanding titles it has proved impossible to separate them so we recommend splashing out and getting both. Trump, Farage the #brexit fallout, has seen a revival of a right wing populism built round a naked racism, and with Le Pen 2017 could be worse still. What we desperately need is a popular anti-racism, not talking to each other to confirm our own opinions but to reach out, not pandering to the haters and the misinformed but conversing and where required challenging too. Daniel Rachel’s superb Walls Come Tumbling Down chronicles one such effort, via music, from Rock against Racism via 2-Tone to Red Wedge. A period when pop and politics, including Labour, learned how to work together towards what both understood in different ways as the common good.

And our book of the seasonal quarter, our number one for Santa’s red list? Well we have two not one because we’ve chosen a theme and there is a pair such outstanding titles it has proved impossible to separate them so we recommend splashing out and getting both. Trump, Farage the #brexit fallout, has seen a revival of a right wing populism built round a naked racism, and with Le Pen 2017 could be worse still. What we desperately need is a popular anti-racism, not talking to each other to confirm our own opinions but to reach out, not pandering to the haters and the misinformed but conversing and where required challenging too. Daniel Rachel’s superb Walls Come Tumbling Down chronicles one such effort, via music, from Rock against Racism via 2-Tone to Red Wedge. A period when pop and politics, including Labour, learned how to work together towards what both understood in different ways as the common good.  But no such effort would have been remotely possible without the singular experience of Rocking against Racism a story now retold via Reminiscences of RAR edited by two who set it all up, Red Saunders and Roger Huddle. This a book full of such sublime enthusiasm and vision it can only leave the reader wondering why nothing remotely like it has come again and what we can do in 2017 to make that happen. Daniel Rachel’s book will help convince us of the pitfalls of simply recreating the past, Roger and Red’s that despite this when culture and politics click anything is possible. Now that’s one Christmas present worth having.

But no such effort would have been remotely possible without the singular experience of Rocking against Racism a story now retold via Reminiscences of RAR edited by two who set it all up, Red Saunders and Roger Huddle. This a book full of such sublime enthusiasm and vision it can only leave the reader wondering why nothing remotely like it has come again and what we can do in 2017 to make that happen. Daniel Rachel’s book will help convince us of the pitfalls of simply recreating the past, Roger and Red’s that despite this when culture and politics click anything is possible. Now that’s one Christmas present worth having.

Note No links in this review to Amazon, if you can avoid buying from tax dodgers, please do so.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ akaPhilosophy Football

We Were Their Flowers in the Dustbin

26.11.2016

40 years ago today The Sex Pistols' Anarchy in the UK was released. Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football remembers.

For some of us of a certain age it still seems like yesterday. For others it is something to breathlessly boast to our children, or grandchildren, that yes, we were there. 26th November 1976, the Sex Pistols release their debut record Anarchy in the UK and for as long as the 7-inch single (remember those?) was on the turntable (ditto) it was as if the world had changed, forever.

Back in ’76 I was anything but a teenage muso. Whilst others raved about Pink Floyd, Bowie, Fleetwood Mac and the like I remained musically nonplussed. Meantime the teenybop phenomenon of David Cassidy, the Osmonds, the Bay City Rollers were as meaningless to me as their fictional televised version, The Partridge Family. Rock n Roll was growing old minus the disgracefulness bit. And then the Pistols appeared on London Weekend TV. I was about to have supper, my parents were in the kitchen and I was sent to the lounge to switch the television off. It was incredible, a bunch of misbehaving teenagers, the Pistols, Siouxsie Sioux, the Bromley contingent, telling the disbelieving presenter , Bill Grundy, exactly what they thought of him and his hated establishment with every swear word that I knew enough shouldn’t be used in polite company let alone live on ITV. Thankfully my parents hadn’t heard what I’d heard but I had, every bit of it. My mind wasn’t exactly on supper that evening.

Their TV appearance not only catapulted the Sex Pistols into the headlines the musical movement they represented, punk, sparked a moral panic. Of course youth culture had done this before back in the 1950s with the Teddy Boys or the 1960s Mods vs Rockers and most recently early 1970s hippy psychedelia. But by the mid 1970s British politics was in such a state of flux this panic seemed to be of a different order entirely. The miners had been on strike not once, but twice, 1972 and ’74, defeating the Tory government on both occasions. The army were brought in, unsuccessfully, to break both the fire brigades and dustbin workers when they went on strike. They failed. The fascist bootboys of the National Front were on the march and chalking up big votes too, facing fiercely ferocious opposition wherever they appeared. The Police were using ‘Sus’ laws, stop and search, provoking a militant backlash. And the opposition Conservative Party was describing immigration as ‘swamping’ our culture.

The Pistols, with their foul mouths, wilfully out-of-tune music and whining vocals, torn to shreds clothing and safety pins through their earlobes were a two-fingered response to any Establishment attempt to paper over the cracks of this crisis. ‘ We’re the flowers in the dustbin, we’re the poison in your human machine.’ Most if us didn’t know the word at the time but this was a very English nihilism,. ‘Destroy’ as the Pistols’ sang and their T-shirts demanded.

The nihilism wasn’t politically located in any obviously Left v Right sense though the Left liked to think it was because Punks were against the same establishment they were opposed to as well. With the National Front in the shadows there was no guarantee that this propensity to destroy would take a progressive dimension. Not helped either by the Punks’ readiness to wear the swastika as a symbol of the anti-establishment, flirt with Nazi themes in the so-called cause of dissident art and the essential whiteness of the bands and most of their followers. What made this musical moment so special was that not only was any risk of punk’s nihilism becoming a popular force for ugly reaction firmly quashed but an alternative set of connections centred on being both anti-nazi and against racism erected in its place.

This was the unique achievement of late 1970s punk. It became almost indivisible from Rocking against Racism, a movement shortly to be chronicled in a brilliant new book Reminiscences of RAR, and marching against the National Front behind the punked up slogan ‘ Nazis are No Fun.’ Make no mistake the nihilism of punk could have gone either way but it didn’t and a musical movement of change was created, from below, for perhaps the first, and disappointingly to date, the last time. More than any single band or performer The Sex Pistols were emblematic of that moment and the contradictions therein. They ignited the idea that just about anyone could form a band, put on a gig, write and publish a fanzine. Every city, town, village would generate its own version of what Punk was and might become. Rock against Racism fed into this, anybody could join because there was nothing to sign up to, no membership form, no committee, just a movement we made our own. A musical, and political, attitude that matched the needs and aspirations of each other. And without the Pistols none of that would have been possible A bit of eff you with a lot of do-it-yourself. We meant it maaan… and still do !

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled 'sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction, aka Philosophy Football. Their range of 40th Anniversary Pistols’ T-shirts are launched today and available from here.

A Poppy for Our Thoughts

11.11.16

Ahead of the England vs Scotland game Mark Perryman responds to FIFA’s Poppies ban

The last time England played Scotland in a competitive match at Hampden Park was also in November, 1999, it was preceded by none of the manufactured row about whether the teams should have poppies embroidered on their shirts. The tabloids were more interested in a good old-fashioned football rivalry instead. The Sun greeting the fixture with the headline ‘Jocks Away’ while north of the border the Daily Recordsought to put England manager Kevin Keegan’ over-confidence in its place ‘Boastbusters’ with the unforgettable tagline ‘ Scots v The Auld Enemy : See Pages 2,3,4,5,6.7,62,63,64,65,66, 67 & 68.’ This was pre Salmond and Sturgeon, the irresistible rise of the SNP and the near wipeout of Scottish Labour MPs. And it was before UKip’s forward march too,. Culminating in #Torybrexit , a populist version of English nationalism against all things that Europe, and Scotland seems to represent in terms of broadly social-democratic values versus a neoliberal free-for-all.

None of this entirely explains the row over the players’ wearing poppies but it does provide a context . It is the same with the emergence of a warped English patriotism that reduces the heroism and sacrifice of those who gave their lives to defend this country in World War Two to just another football chant ‘Two World Wars and One World Cup’ . Scarcely present in ’66 when England were beating West Germany in the final, with the Charlton brothers in the side who had vivid memories of growing up during bombing raids on Tyneside while a decent chunk of England’s support in the stands were of an age who’d fought in that war too. Instead the chants emerged after England’s loss to West Germany on penalties at Italia ’90, cranked up again by the same result to the same opponents at Euro ’96. And all this during an era when euroscepticism led by John Major’s ‘bastards’ opposition on the Tory benches emerged to force a key dividing line in British politics.

This is the context for the current row . An act of remembrance is not of itself political. But who are we rememberjng? What did they fight for ? Where did they come from to join that fight? The clue is in the title of the two conflicts being marked World Wars One and Two. Britain had a special role as combatants in both but we were not alone. The teams of France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway, or from further field the Commonwealth countries, the USA, USSR are not clamouring to wear a poppy on their shirts this November. When it becomes all about just the home nations while playing internationals the meaning inevitably changes.

FIFA bans all political symbols from adorning any national kits. The Irish are threatened with being punished for embroidering the Easter Rising centenary on to theirs. Almost every FIFA-affiliated country could make a similar case from South Africa and Israel via Armenia and Palestine to Syria and the Ukraine. The Tuesday after England play Scotland they take on Spain in the 80th anniversary year of British and others countries’ volunteers travelling to Spain to join the defence of the Spanish Republic against Franco’s fascists. Is the FA suggesting the England team wear something to mark this special moment of solidarity between our two countries? No, no such suggestion. Some symbols are OK. Others not, a choice made by politics.

We cannot escape the fact that sport is political, it is a contest just like the one on the pitch. Currently in American sport there is a growing movement of athlete-activism . The NFL player Colin Kaepernick kneeling respectfully but defiantly during the playing of the National Anthem because for millions of Americans, despite Trump, #BlackLivesMatter. When USA Women’s Football International, World Cup winner and Olympic Football Gold medallist Megan Rapinoe did the same whilst representing her country she was doing something unheard of over here.

Or maybe not. Gary Lineker has been hounded by the tabloids for his views on refugees not just because for what he is saying, but for who he is and was. A footballer, with views, with politics ? What right does he have to hold such opinions? But of course sport is full of opinions, some of which we agree with others we don’t.

I won’t attempt to predict the England v Scotland score but two things I can be certain of. There won’t be a single Union Jack waved by England fans whereas 50 years ago when England hosted the World Cup the FA managed to get the host country’s flag wrong on all official publicity, the Union Jack not the St George Cross . And there will be plenty of chants inviting the Scots impolitely to stick Nicola Sturgeon somewhere rude. That last time these two teams met in a competitive match, back in '99, I doubt many could have named the SNP leader let alone be much bothered about him.

My beef isn’t with the poppy nor acts of remembrance. The state-sanctioned patriotism serves to obscure the consequences of carnage from the causes of conflict but that is something to contest not retreat from. The argument should be bigger than this annual dust-up over the poppy. It is about breaking down the false division between sport and politics, to recognise that all sport is political, and for those of us with a progressive vision we have a role in shifting those politics on, and off the pitch, from the reactionary to our side, whatever team we support or none.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ akaPhilosophy Football from where the 1914 Poppies Remembrance T-shirt is available.

They Did Not Pass

04.10.16

Eighty years ago, 4th October 1936 and Oswald Mosley was preparing to lead a parade of hate. His British Union of Fascists were to march through London's East End home to the Capital's single largest Jewish community. The Blackshirts intent was clear, to spread fear and terror with their vile and violent ant-semitism. Except they didn't. They coudn't because on that day 100,000 Eastenders turned out, of all faiths and none, to stand with their Jewish neighbours and at Cable Street first they stopped the Fascists and then forced them into humiliating retreat. They did not pass.

For the anniversary Philosophy Football's specially-made short film combines archive images soueced by David Rosenberg author of Rebel Footprints : Uncovering London's Radical HIstory with a Heaven 17 soundtrack of We Don't Need That Fascist Groove Thang. In music and pictures against fascism then,now and forever.

The Philosophy Football 80th anniversary Cable Street T-shirt is available from here

The Philosophy Football 80th anniversary Cable Street T-shirt is available from here

Our Front is Popular

15.09.2016

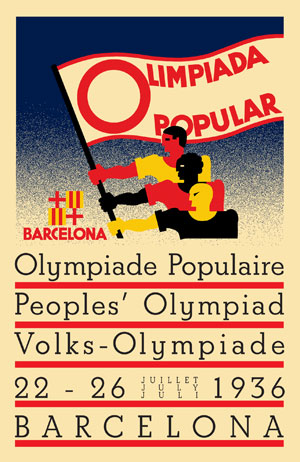

Mark Perryman revisits 1936 when anti-fascism was the cause home and abroad

‘ Hurrah for the Blackshirts!’ The notorious Daily Mail headline is just one chilling indication of the very real threat Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists posed in the mid 1930s. Inspired by the successful rise to power of Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany Mosley sought to galvanise support via a combination of naked anti-semitism and brute force. By 1936 he was attracting both well-heeled establishment support and thousands to his rallies where any protests would be dealt with violently and without scarcely any intervention by the police.

On 4th October 1936 Mosley planned the BUF’s biggest and boldest initiative yet. His uniformed Blackshirts would march through London’s East End, home to one of the country’s largest Jewish communities. The intention was quite clear, to cause fear and stir up hate. On the day more than a hundred thousand East Enders turned out to protect their community, of whatever faith or none. The fascists were forced to retreat. They did not pass. But there was also a realisation that protest alone would not stop the hateful ideas that Mosley sought to encourage as a vicious diversion from the causes of the East End’s very real problems. Phil Piratin, one of the key organisers of the Cable Street protest, argued successfully that the key to the area’s problems was poor housing, slum landlords, steep rent rises and evictions. He helped organise tenants, including those with BUF sympathies, separating the cause of their living conditions from the lies the fascists spread. Piratin was a Communist, in the 1945 General Election just nine years after the Fascists thought they could rule the East End he was elected the Communist MP for Stepney.

On 4th October 1936 Mosley planned the BUF’s biggest and boldest initiative yet. His uniformed Blackshirts would march through London’s East End, home to one of the country’s largest Jewish communities. The intention was quite clear, to cause fear and stir up hate. On the day more than a hundred thousand East Enders turned out to protect their community, of whatever faith or none. The fascists were forced to retreat. They did not pass. But there was also a realisation that protest alone would not stop the hateful ideas that Mosley sought to encourage as a vicious diversion from the causes of the East End’s very real problems. Phil Piratin, one of the key organisers of the Cable Street protest, argued successfully that the key to the area’s problems was poor housing, slum landlords, steep rent rises and evictions. He helped organise tenants, including those with BUF sympathies, separating the cause of their living conditions from the lies the fascists spread. Piratin was a Communist, in the 1945 General Election just nine years after the Fascists thought they could rule the East End he was elected the Communist MP for Stepney.

Within weeks of Cable Street the Spanish Civil War that had begun in July with Franco’s armed rebellion against the democratically elected Republican Government led to the formation of the International Brigades. Travelling to Spain, mostly with next-to-no military training, British volunteers went there to join the country’s battle for land and freedom against Franco’s fascism. An internationalism which was criminalised by their own government which backed instead a useless policy of non-intervention while Hitler and Mussolini armed unimpeded their Spanish ally Franco. Preceding the International Brigades foreign volunteers simply formed units to help defend the Republic, amongst the first was the Tom Mann Centuria made up of Brits living and working in Barcelona. Once the British Battalion was officially formed it joined the 15th Brigade which was primarily, though not exclusively, English-speaking. The fighting Spanish forces included Catalan nationalists , anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists and parties such as the POUM which George Orwell famously fought alongside. All were united however, for the most part, in what was known as a ‘Popular Front’ led by socialists and communists.

In 1938 the International Brigades left Spain and within less than a year Franco had completed his victory, a fascist regime installed in Spain. Shortly after Hitler invaded Poland, World War Two began. On the Brigade’s departure the Communist MP Dolores Ibárruri, known forever as La Pasionaria, spoke, her words remain an inspiration for all those who resist oppression, wherever, whatever, whenever.

“It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees."

The Popular Front which inspired both those who stopped the Blackshirts at Cable Street and those who joined the International Brigades was based on a simple idea. Concentric circles of unity. At its centre was the working-class movement, in the 1930s this was most notably the Communists, around which was formed a broader anti-fascist People’s Front. And by World War Two this became a National-Popular Front in those countries determined to resist Hitler, Mussolini and Imperial Japan, eventually with the USSR’s entry into the war in 1941 this took on the dimension of an International Front too.

Two of the key objectives of the Popular Front were outlined by the architect of the strategy, Bulgarian Communist Georgi Dimitrov.

“ Find a common language with the broadest masses as well as overcoming the fatal isolation of the working class itself from its natural allies.”

Eighty years on in a much-changed era for a radical politics of opposition they are principles that nevertheless remain as relevant as ever for all those committed to rebuilding a Popular Left.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football. Our range of 1936 Popular Front T-shirts is available from here.

Social-democratic Team GB success vs Freemarket England Football Team Failure

22.08.2016

Mark Perryman outlines what Team GB's Olympic success does and does not mean

Team GB’s second place in the Rio medals table is nothing less than staggering. It is only 20 years ago that the squad returned with a solitary Gold from Atlanta ’96 clinging on to 36th in the table..This sporting nation is now ranked alongside the Olympian superpowers of USA and China. If it hadn’t been for the partial IOC ban on their competitors Russia would have been in the mix too but still this remains a remarkable Team GB medal haul.

Unlike the football World Cup the Olympics Medal Table is by and large an indicator of global economic and political power. These superpower natiions, USA, China and Russia, cannot claim a single men’s Football World Cup title between them or have come anywhere but close, mostly. The Olympics is different. So how has Team GB ended up on top of the Olympic pile?

20 years ago apart from Atlanta '96 there was Euro '96. England's last semi-final appearance at a tournament, Scotland went out at the Group Stage and apart from France '98 have failed to qualify since. Wales and Northern Ireland each had magnificent France 2016 campaigns this summer but apart from that the record has been pretty dismal. For England and a sport which, despite all the evidence, we like to think we rule the world the contrast with Team GB's recovery over those same two decades is startling.

The reasons are not so much in further, faster, higher than a victory of social-democracy vs neoliberalism. Yes that’s right. Via the Lottery all the most successful Team GB Olympic sports are state –subsidised. A huge investment, £350 million over the Olympic Cycle, or around £5.5 million per Medal won. But the values of social democracy that pervade this sporting success go further. The funding is subject to regulatory governance, of collective endeavour and accountability. The Olympic Sports entirely control the regime their athletes train and compete under with a relentless pursuit of Olympic success as the pinnacle of all achievement, if necessary at the cost of other competitions and honours.

The reasons are not so much in further, faster, higher than a victory of social-democracy vs neoliberalism. Yes that’s right. Via the Lottery all the most successful Team GB Olympic sports are state –subsidised. A huge investment, £350 million over the Olympic Cycle, or around £5.5 million per Medal won. But the values of social democracy that pervade this sporting success go further. The funding is subject to regulatory governance, of collective endeavour and accountability. The Olympic Sports entirely control the regime their athletes train and compete under with a relentless pursuit of Olympic success as the pinnacle of all achievement, if necessary at the cost of other competitions and honours.

English football represents the total opposite. Here neoliberalism rules. Far more money is splashed about. £350 million? That wouldn’t be far off just one Premier League club’s transfer and wages budget for a single season. For what? The ‘best league in the world’ (sic) is going backwards in terms of mounting a serious challenge to win the Champions’ League. And as the recent Euro 2016 Final proved the finest players in Europe, and this was also true of the World Cup 2014 Final too, the world as well, by and large play outside of England too. In classic neoliberal fashion the ‘richest league’ in the world has been wilfully mistranslated in to the ‘best league’ in the world.

But the biggest marker of this failure is the England football team. All the riches in the world and they cannot get past Iceland, or at World Cup 2014 out of their group. The sport’s governing body, the FA, has engineered the total deregulation of their own sport. Every club out for their own end. Private money chasing individual gain, no collective endeavour, zero accountability, hands-off governance The result is a catalogue of failure.

No Olympic sport would permit such an abdication of responsibility and thus the big result from Rio can’t simply be measured in the mountain of Gold, Silver and Bronze medals but eam GB’s social democratic values beating the freemarket failure of English football hands down.

However the social-democratisation of Team GB is flawed in one crucial respect. The £350 million bill has given those that enjoy their sport from the sofa a glorious two and a bit weeks. A quadrennial celebration of sport few will forget in a hurry. But while there will be a spike of interest in doing some of these sports without the infrastructure and funding to meet the largesse splashed out on the elite level this will be short-lived. This isn’t to decry the Gold Medals. But we need a political conversation – this is about political choices – that makes the connection between a social democratic sports culture for some with one that is for all. To recognise that while TV viewing figures soar, the front page celebrations of Olympic success become a daily occurrence and the Gold Medal feelgood factor hits the heights none of this is enough to sustain a fundamental change in sport and leisure culture.

Team GB has helped prove what an impact public expenditure combined wity regulation towards a collective end can achieve. And precious few complain, we wallow in the success as much theirs, the athletes', as ours' too. But this race won’t truly be won until those resources are mobilised towards creating a sports and leisure culture that serves sport for all, and not just for some. If public expenditure is good enough to fund winning Gold Medals then isn’t it good enough to fund the return of school playing fields, build public swimming pools, construct jogging and exercise trails too.

Philosophy Football's unique, strictly unofficial, Team GB Rio Medals Table T-shirt is available from here

Mark Perryman, co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction, aka Philosophy Football, and author of Why The Olympics Aren’t Good For Us : And How They Can Be.

More of a Marathon than a Sprint

08.08.16

Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football offers his reading selection for a Summer of Sport

Exhaustive? Exhausting more like. The never-ending summer of sport from Euro 2016, the British Grand Prix, English rugby down under, Test Match cricket, Le Tour, Wimbledon fortnight , Rio 2016 and then before you know it the football season has started. It was ever thus, the sport has just got bigger that’s all, if not always better.

To help navigate our way thought the cause and effect of the highs and the lows there’s no better place to start than John Leonard’s Fair Game an easy-to-read history of the clash between politics and sport. To take a more philosophical approach means engaging with competition vs participation, another one of those big match this versus that binary opposition which serve more to obscure than inform. Losing It by the superlative Simon Barnes teaches us more than we will ever need to know about the joys of not being on the winning side. But the sharpest divide in sporting culture has nothing to do with winners and losers but gender. Name a single sporting culture which isn’t fundamentally shaped by gender relations. Anna Kessel’s Eat Sweat Play is a popular read on a subject of complexity which reveals the structures that shape this sporting determinism. An absolutely essential read for the future of sport, any sport.

To help navigate our way thought the cause and effect of the highs and the lows there’s no better place to start than John Leonard’s Fair Game an easy-to-read history of the clash between politics and sport. To take a more philosophical approach means engaging with competition vs participation, another one of those big match this versus that binary opposition which serve more to obscure than inform. Losing It by the superlative Simon Barnes teaches us more than we will ever need to know about the joys of not being on the winning side. But the sharpest divide in sporting culture has nothing to do with winners and losers but gender. Name a single sporting culture which isn’t fundamentally shaped by gender relations. Anna Kessel’s Eat Sweat Play is a popular read on a subject of complexity which reveals the structures that shape this sporting determinism. An absolutely essential read for the future of sport, any sport.

Once every four years the Summer Olympics are so huge that for two and a bit weeks they both block out almost all other sport, and plenty more besides while providing a platform for sports that otherwise hardly ever get a look in. The latter is arguably one of the few remaining redeeming features of the Olympic ideal.

Dave Zirin’s fully updated Brazil’s Dance with the Devil deals with all these other less redeeming, anything but ideal, features of both the Olympics and football’s World Cup and their impact on Brazil in 2014 and 2016. Of course most of these failings are not new, from Jules Boykoff Power Games is a political history of the Games which explains the scale of the failure both historically and theoretically via the highly original concept of ‘celebration capitalism’. During Rio this will be our fayourite read between the breathlessly exciting sporting action on the TV.

Dave Zirin’s fully updated Brazil’s Dance with the Devil deals with all these other less redeeming, anything but ideal, features of both the Olympics and football’s World Cup and their impact on Brazil in 2014 and 2016. Of course most of these failings are not new, from Jules Boykoff Power Games is a political history of the Games which explains the scale of the failure both historically and theoretically via the highly original concept of ‘celebration capitalism’. During Rio this will be our fayourite read between the breathlessly exciting sporting action on the TV.

Ordinarily the combination of a European Championships and the fiftieth anniversary of ’66 would have turned 2016 into a footballing summer. For the English at any after Iceland 2 Poundland 1, no chance. Peter Chapman’s exercise in nostalgia Out Of Time reminds us of a year when for England, almost anything seemed possible, on and off the pitch, 1966. A perhaps less obvious year to choose to revisit with such English optimistic intent is 1996. But this was the year of England’s Euro 96, Britpop (actually English pop) and new Labour on the eve of a General Election landslide, including a majority of English seats. When Football Came Home by Michael Gibbons and When We Were Lions from Paul Rees both cover this epic tournament with one eye on the politics and culture of the time too. For thirtysomethings and older a really great read about something England have failed to do this century, make it to a tournament semi-final! Taking a longer historical view is Colin Shindler’s Four Lions which imaginatively chronicles English footballing history via the life, career and times of four England captains; Billy Wright, Bobby Moore, Gary Lineker and David Beckham. Taking a more conventional approach to all things post ’66 Henry Winter in Fifty Years of Hurt records with the finest of insights all that has gone wrong, and the reasons why, since that singular golden moment five decades ago. The paperback edition will make even more painful reading mind no doubt with he defeat to Iceland tacked on and the dawning of the age of Big Sam as England supremo. For a variety of studies of the modern game the edited collection by Ellis Cashmore and Kevin Dixon Studying Football provides a richness of academic explanations which are both rich in detail and deep in understanding.  But my top choice to pack for the new season’s away trip reading has to be And The Sun Shines Now by Adrian Tempany. I first read this superb book a year ago, cover-to-cover a review copy in just a few sittings but then it was promptly withdrawn because of the Hillsborough Inquest. This is a book you see that begins and ends with Hillsborough and in between deals with the mess modern English football has become. Delayed because of the Inquest and the legal restrictions of the legal proceedings on such a book, twelve months later it is if anything an even more powerful and compelling read.

But my top choice to pack for the new season’s away trip reading has to be And The Sun Shines Now by Adrian Tempany. I first read this superb book a year ago, cover-to-cover a review copy in just a few sittings but then it was promptly withdrawn because of the Hillsborough Inquest. This is a book you see that begins and ends with Hillsborough and in between deals with the mess modern English football has become. Delayed because of the Inquest and the legal restrictions of the legal proceedings on such a book, twelve months later it is if anything an even more powerful and compelling read.

Without the Ashes cricket struggles to get much of a look-in even during the summer months, selling off the live TV coverage to Sky has reduced wider public interest still further. Emma John’s Following On is therefore a timely reminder of cricket’s appeal, even when it’s not very good.

Football of course has been dominant for so long now in English sporting culture it is hard to imagine other models for how to consume sport, a five-day Test Match perhaps the most incongruous alternative imaginable. For me though my favourite other way to consume sport is cycling. Decentralised, free to watch, pan-European, on terrestrial TV, thousands ride the course to reach their best roadside vantage point, and the Brits always win, well almost. I’m talking of course about Le Tour. The classic account of this most famous of cycling contests, Geoffrey Nicholson’s The Great Bike Race, has recently been republished and is as good as it ever was, a superb mix of cultural history and sporting commentary.  And a novel to expand our understanding of what it takes to ride this greatest of all races? From Dutch author Bert Wagendorp now translated into English Ventoux the story of a group of friends who decide to ride to the summit of this most iconic of climbs and the effect the effort has on all of their lives. The Science of the Tour de France by James Witts takes a more practical approach. In spellbindng detail along with magnificent photography and graphics the author carefully explains what it takes to ride this most punishing of races spread over almost an entire month of varied and arduous competition. There is probably no rider better equipped to put that experience into words than David Millar, and he does precisely that in his very fine new book The Racer.

And a novel to expand our understanding of what it takes to ride this greatest of all races? From Dutch author Bert Wagendorp now translated into English Ventoux the story of a group of friends who decide to ride to the summit of this most iconic of climbs and the effect the effort has on all of their lives. The Science of the Tour de France by James Witts takes a more practical approach. In spellbindng detail along with magnificent photography and graphics the author carefully explains what it takes to ride this most punishing of races spread over almost an entire month of varied and arduous competition. There is probably no rider better equipped to put that experience into words than David Millar, and he does precisely that in his very fine new book The Racer.

What is special about cycling is the connection between competition and participation, what other sport can you use as a means to get to work, do the shopping, a family day out? Team Sky rider and Team GB Olympian sketches out precisely those connections in his amusing yet informative book The World of Cycling According to G .

The most basic sporting test however of human endurance remains running. Arguably the one truly universal global sport, requiring no equipment, no facilities, any body shape, and for the lucky few a route out of poverty too. Richard Askwith has established himself as one of the best writers on the sport, Today We Die A Little is Richard’s biography of one of the greatest long-distance runners of all time, Emil which reveals both what it takes physically to take one’s body beyond the limits of human endurance but also the political context of 1950s Eastern Europe which drove Zátopek to run. A truly illuminating read. But there’s one feat Zátopek failed to achieve, nor any runner after him either. Breaking two hours for the marathon. Ed Casear’s Two Hours combines investigative journalism, sports science and athletic travelogue to find out whether this near-mythical barrier might ever be broken.

Richard Askwith has established himself as one of the best writers on the sport, Today We Die A Little is Richard’s biography of one of the greatest long-distance runners of all time, Emil which reveals both what it takes physically to take one’s body beyond the limits of human endurance but also the political context of 1950s Eastern Europe which drove Zátopek to run. A truly illuminating read. But there’s one feat Zátopek failed to achieve, nor any runner after him either. Breaking two hours for the marathon. Ed Casear’s Two Hours combines investigative journalism, sports science and athletic travelogue to find out whether this near-mythical barrier might ever be broken.

And my sports book of the quarter? There is only really one choice. Not content with writing a peerless global history of football, The Ball is Round and a riveting account of all that is wrong with English football The Game of Our Lives David Glodblatt has now written both the definitive and best history of the Olympics, The Games. What David does so effortlessly well as a sportswriter is combine hard won facts and tales with original opinion and ideas to construct both a story and an alternative. The must have book for those late nights and early mornings on Olympics TV watch from Rio, and long after too.

And my sports book of the quarter? There is only really one choice. Not content with writing a peerless global history of football, The Ball is Round and a riveting account of all that is wrong with English football The Game of Our Lives David Glodblatt has now written both the definitive and best history of the Olympics, The Games. What David does so effortlessly well as a sportswriter is combine hard won facts and tales with original opinion and ideas to construct both a story and an alternative. The must have book for those late nights and early mornings on Olympics TV watch from Rio, and long after too.

Note: No links in this review toAmazon, if you can avoid purchasing from tax dodgers please do so.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football.

A Games That Belonged To The People

05.08.2016

Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football uncovers the hidden history of Barcelona ‘36

When the Rio Olympics begin tonight beyond the glitz and the glamour of the opening ceremony spectacle there will be popular protests right across the city. It was the same at London 2012 and the Vancouver Winter Games of 2010. Throughout the build up to both Sochi 2014 and Beijing 2008 there were global protest to force attention on LGBT discrimination and human rights issues in host countries Russia and China. But of course once the gold medal rush began the protests and concerns were almost universally marginalised. I suspect it will be more or less the same with Rio.

How do we manage both to enjoy and celebrate sport while maintaining some basic principles of equality and solidarity? Perhaps what we need is a political culture that takes sport seriously – what we do with Philosophy Football mixing sport and culture is one brave and audacious attempt to do precisely that – rather than treating it simply as a suitable add on for photo opportunities and celebrity endorsements of this issue or that.

For an idea of what might be possible a useful starting point would be to revisit the 1930s. This was of course the era of the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. Mussolini put great emphasis on football as the means of portraying his idealised fascist nation, Italy hosted and won the 1934 World Cup and retained the trophy four years later too at France ’38 on the eve of war. But it is Hitler’s Berlin Olympics of 1936 which are most widely remembered for the clash of political ideology and sporting spectacle. The four gold medals won by black American sprinter and long jumper Jesse Owens of course have come to symbolise the way sport can subvert an intended political message to devastating effect. But what scarcely gets mentioned is the widespread efforts of both the International Olympic Committee to make a positive case for the Nazi regime to host the Games in order to head off calls to boycott Berlin.Much of this lobbying was done by notorious anti-semite Avery Brundage who went on to become the President of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. This is the history the Olympic movement would prefer remained hidden.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

The Spanish Republican government took a political decision to boycott the Berlin Games. They correctly judged that with the Olympic movement barely interested in putting up any opposition Berlin would become a platform for Hitler and Goebbels to sanitise and propagandise for Nazism. Jesse Owens notwithstanding, they were proved absolutely correct. However this was no ordinary boycott. The Spanish government pledged to host a People’s Olympiad in the Republican stronghold of Barcelona with over 6,000 athletes from across the world taking part. Timed to take open just a few weeks before Berlin this would have been a powerful example in practice of a sporting internationalism vs the racialisation of sporting endeavour the Nazis were seeking to promote. Then, on the eve of the opening ceremony, Franco launched his murderous assault on the Spanish Republic, the country was plunged into civil war and the Games cancelled. Most athletes were forced to leave though some chose to stay and join the International Brigades in their fight for Spain’s land and freedom.

The point about Barcelona ’36 is that it didn’t happen in isolation. Other ‘alternative’ Games included Czechoslovakia’s 1924 National Gymnastics Festival organised by the Workers Gymnastics and Sports Association, the first Workers’ Olympics in Frankfurt 1925, Moscow’s Spartakiad of 1928, the Vienna Workers’ Olympics of 1931, a second Spartakiad of 1933 organised by the Red Sport International, the third and final Workers’ Olympics, Antwerp 1937. And there were alternative Women’s Olympics too, four in all 1922 Paris, 1926 Gothenburg, 1930 Prague and 1934 London.

It’s almost impossible to imagine anything of this scale of imagination and purpose today. Jules Boykoff in his brilliant new political history of the Olympics, Power Games, has a novel explanation of why such an alternative model of sport is so important rather being being simply, if necessarily, against this and that. He describes the Olympics, and other global sporting spectacles such as football’s World Cup, as ‘celebration capitalism’ juxtaposing this to Naomi Klein’s theorisation of ‘disaster capitalism’. For the duration of Rio we will be treated over and over again to the Olympian maxims of inspiration, regeneration and participation. Huge public and material investment in infrastructure and Gold Medal-winning performances to celebrate what, and benefit whom? To state this is to engage with a popular common sense,, not to moan and whinge about what Rio 2016 or London 2012 fail to achieve but to be inspired by Barcelona ’36 to shape a better sporting culture for all.

Philosophy Football’s Barcelona ’36 T-shirt is available from here

Don't Burn the Books

08.07.2016

A scorching hot list of summer political reading selected by Mark Perryman

A year ago as Labour sought to recover from the May General Election defeat halls were starting to fill up for Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership campaign rallies. But even as the halls got bigger and the queues round the block longer few would ever imagined that this would result in the Left for once being on the winning side. The overwhelming majority of Labour MPs never accepted the vote, they bided their time and chose the moment for their coup and in a fashion to cause maximum damage.

Richard Seymour’s Corbyn : The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics is to date both the best, and the definitive, account of what Corbyn’s victory the first time round meant. One year on the essential summer 2016 read.

Richard Seymour’s Corbyn : The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics is to date both the best, and the definitive, account of what Corbyn’s victory the first time round meant. One year on the essential summer 2016 read.

But as Jeremy Corbyn would be the first to admit his victory will never amount to much unless he can refashion what Labour also means. A Better Politics by Danny Dorling is a neat combination of catchy ideas and practical policies towards a more equal society that benefits all. Of course the principle barrier to equality remains class. In her new book Respectable Lynsey Hanley provides an explanation of modern class relations that effortlessly mixes the personal and the political. If this sounds easier written than done then George Monbiot’s epic How Did We Get Into This Mess? serves to remind us of the scale of the economic and environmental crisis we are up against.Labour’s existential crisis is rooted in competing models of party democracy and how this should shape a party as a social movement for change. An exploration of what a left populist mass party might look like and the problems it will encounter is provided in Podemos: In the Name of the People a highly original set of conversations between theorist Chantal Mouffe and Íñigo Errejón political secretary of Podemos, introduced by Owen Jones, what a line-up!

One of the saving graces of Labour’s crisis should be pluralism. To reject those who indulge in the simplistic binary oppositions of Corbynista vs Blairite. To begin with all engaged in the Labour debate should read the free-to-download book Labour’s Identity Crisis : England and the Politics of Patriotism edited by Tristram Hunt. There is much here on an issue vital post #Brexit yet scarcely acknowledged as important by most on both ‘sides’ One criticism though, why no contributors from the Left side, Billy Bragg, Gary Younge, the young black Labour MP Kate Osamor for example? Taking a tour round Britain to portray the state of the nation(s) is fairly familiar territory for writers on Britishness but Island Story by JD Taylor still manages to stand out thanks to a the author’s sense purpose, tenacity of the imagination, and a bicycle. Underneath the surface of any tendency towards a settled national narrative lies a bastardised version of English nationalism combining the isolationist and the racist to produce a toxic mix. As a shortish polemic The Ministry of Nostalgia from Owen Hatherley is more of a demolition than a deconstruction of the rewriting of our history that lies behind this, and all the better for it.

Anglo-populism is mired in the issue of immigration as a mask for its racism.Angry White People by Hsiao-Hung Pai encounters the extremities of this, the Far Right whose politics of hate have a nasty habit of not being as far away as many of us would like.In the USA the brutal institutionalised racism of its police force has sparked a mass movement which is reported with much insight by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s in her From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, an essential read if a similar popular anti-racism is going to emerge on this side of the Atlantic sometime soon. Of course #BlackLivesMatter didn’t emerge in a political vacuum, it connected movements that date back to the 1950s and 1960s, connections which are expertly made by one of the key Black political figures of both then and now Angela Davis in her new book Freedom is a Constant Struggle an absolutely inspiring read. Do the deepening fractures around race spell a new era of uprisings? Quite possibly though their political trajectory and outcomes remain uncertain. Joshua Clover comes down firmly on the side of the optimistic reading in his new book Riot.Strike.Riot while most wouldn’t be so sure. A handy companion volume would be Strike Art by Yates McKee which helpfully explains the protest culture created via the Occupy movement. Where the doubt remains is whether the such moments, direct action or insurrection, can generate a positive impact beyond their own milieu or locality.

Shooting Hipsters is a much-needed up to date account of, and practical guide to, how acts of dissent can breakthrough into and beyond the mainstream media. And for the dark side? Mara Einstein’s Black Ops Advertising details the many ways in which corporate PR operations have sought to colonise social media.

Shooting Hipsters is a much-needed up to date account of, and practical guide to, how acts of dissent can breakthrough into and beyond the mainstream media. And for the dark side? Mara Einstein’s Black Ops Advertising details the many ways in which corporate PR operations have sought to colonise social media.

It is out of history that inspiration for how to carve out a better future from the present is most likely to come. A Full Life by Tom Keough and Paul Buhle uses a comic strip to illustrate the life, times and ideals of Irish rebel James Connolly. Alternatively enjoy the extraordinary range of writing from the Spanish Civil War compiled by Pete Ayrton in No Pasaran! These were moments in a period of global change. Owen Hatherley’s carefully crafted The Chaplin Machine provides an insight into the aesthetic of revolution that was abroad at the time in the immediate aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution on a scale never seen before, or since. It is a period that is recorded with considerable skill by the twice-yearly journal Twentieth Century Communism the latest edition providing the usual ingenuity of range including Trotsky’s bid to live in 1930s Britain. outline of the basis for a cosmopolitan anti-imperialism. Of course there are plenty who would seek to bury all of this. David Aaronovitch comes to the last rites with his brilliantly written if flawed Party Animals which takes aim with his personal biography at the end of one history. An entirely different perspective is provided by the hugely impressive Jodi Dean and her latest book Crowds and Party an impassioned account of modern protest movements as the enduring case for a mass party of social and political change. Sounds familiar, trite even? Not the way Jodi argues it, mixing an acute sense of history with a visionary future.But the here and now of a super soaraway summer perhaps demands more immediate resources of hope than the promise of a better tomorrow.

My starting point for a today to look forward usually revolves around finding a recipe for a decent supper. Plenty of these to be found in The Good Life Eatery Cookbook with a mix of good-for-you, or more importantly in this instance me, temptingly delicious-looking photography and a philosophy behind it all that reminds me of that good maxim ‘small is beautiful.’ Of course no summer should be complete without a visit to the beach, highly recommended reading for the sun-lounger searching for a dash of a thriller for a mental getaway is Chris Brookmyre’s latest Black Widow which as always with Brookmyre is dark, twisted and entertaining. And for the children? Pushkin Press do the hard work for parents, tracking down the best in European kids’ books, translating, repackaging and producing such gems as Tow-Truck Pluck from the Netherlands. The perfect holiday read for families needing to be cheered up post-Brexit.

And my book of the quarter? Food is never far from most of our minds. Summertime picnics for the fortunate, worrying about what we eat and impact it has on our health for some, the spread of Food Banks testament to the failure of austerity politics. Few writers could appeal to both the modern obsession with food as well as to consciences concerned with those who don’t have enough of it to get by never mind baking off. But Josh Sutton does with his pioneering account Food Worth Fighting For. This is social history that packs a punch while written in a style and with a focus to transform readers into fighting foodies. Brilliant, and incredibly original.

And my book of the quarter? Food is never far from most of our minds. Summertime picnics for the fortunate, worrying about what we eat and impact it has on our health for some, the spread of Food Banks testament to the failure of austerity politics. Few writers could appeal to both the modern obsession with food as well as to consciences concerned with those who don’t have enough of it to get by never mind baking off. But Josh Sutton does with his pioneering account Food Worth Fighting For. This is social history that packs a punch while written in a style and with a focus to transform readers into fighting foodies. Brilliant, and incredibly original.

Note : No links in this review to Amazon, if you can avoid purchasing from off shore tax dodgers please do.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’, aka Philosophy Football.

#More in Common

22.06.2016

Mark Perryman explains why in any match of Hope vs Hate Philosophy Football knows which side we are on

The shocking news of MP Jo Cox's murder has affected us all. A terrible crime that begins with hate for a neighbour because of where they came from. A hate that is amplified by politicians and media to serve their own interests and never mind the consequences. A process that ends with this and who knows even worse to come.

Britain isn’t alone in suffering any of this, a tidal wave of hate-politics is sweeping Europe. The Freedom Party in Austria, Front National in France, AfD in Germany, Jobik in Hungary, Golden Dawn in Greece, Liga Nord in Italy and more. A racism that exploits and encourages division. A populism that offers easy answers to close down the space for difficult questions. A culture that promotes exclusion, intimidation and isolation.

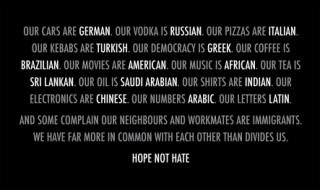

‘Our cars are German, our vodka is Russian, our pizzas Italian…’ Who would ever have imagined that coffee would replace tea as Great Britain’s favourite. Or wine overtake beer as the most popular tipple. Fish and chips vs Chicken Tikka Masala. Cheese and cucumber sarnies vs pitta and humous. Does this mean national identities no longer exist? Of course not. But we co-exist and for the most part are the better off for it.

‘Our cars are German, our vodka is Russian, our pizzas Italian…’ Who would ever have imagined that coffee would replace tea as Great Britain’s favourite. Or wine overtake beer as the most popular tipple. Fish and chips vs Chicken Tikka Masala. Cheese and cucumber sarnies vs pitta and humous. Does this mean national identities no longer exist? Of course not. But we co-exist and for the most part are the better off for it.

Immigration doesn’t happen by accident. We live in a world of bloody wars, extremities of inequality and increasingly the catastrophic social impact of climate change. These more than anything else cause rising levels of movement of population from every part of the world. And on our own continent European youth culture is interconnected in a way unimaginable only a decade or so ago. This is the easyjet generation of twitter, facebook and instagram. Thus living and working in another country is both possible and practical. Immigration? This is about emigration too. A Europe where another country which was once perhaps a holiday destination today provides a workplace.

Interconnections in a Europe of possibilities isn’t what most politicians talk about. In their absence hate fills the gap. That’s why Philosophy Football has always actively backed the Hope not Hatecampaign. While others have done far more than us we made our own contribution. We coined the slogan 'Hope not Hate', designed the logo, produced and donated banners to decorate the Barking cHQ in the succesful 2010 General Election campaign to defeat Nick Griffin and his BNP, helped raise funds and tramped the streets spreading the message. And so when we read that Jo Cox’s friends and family had chosen Hope not Hate as one of the campaigns to donate to in her memory, we wanted to find a means to contribute. Our 2016 Hope not Hate tee is towards that end, raising funds with a new design featuring a message for the better world she believed in.

Jo Cox was rare. She both understood why people move from country to country, some for work, others for safety, many for both. But she also had the courage to challenge these lies about immigration that exploit anxieties with reckless abandon. Inspired by her principles and ideals, our shirt features Jo's words from her House of Commons maiden speech 'We are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divides us'. A simple idea, we’d like to think while not uniquely British, a British value. Getting on with others, pulling together, sharing adversity for the greater good, bold and brave enough to engage with the other, celebrating our differences but not at the expense of one another. In the big match of hope vs hate knowing which side we’d rather be on thankyou very much.

The murder of Jo Cox didn’t come out of nowhere. A single lethal act but out of a mood that seeks to justify, legitimise, give respectability to a politics of hate. One singularly tragic consequence but against a background of countless other acts of hate. If politics is about anything it is about standing up for change, to challenge prejudice and misinformation, a vision of a better society for all. This is how we resist the drift towards the hateful.

Our simple act of remembrance has a practical aim. In place of our customary new shirt discount £5 will be donated for each shirt sold to Hope not Hate. If you can purchase at the solidarity price £10 will be donated. Remembrance and solidarity.

Hope not Hate 2016 shirt available from www.philosophyfootball.com

Campaign details from www.hopenothate.org.uk

- The Death of Innocence

27.12.25 - Thatcherism Today

04.10.25 - Top Ten Books to Understand Labour Conference

26.09.25